Inflation Dynamics in the UK and Bank of England’s struggle to achieve price stability

Dr Muhammad Ali Nasir, an associate professor in Economics at the University of Leeds, provides an expert opinion on inflation and the response of the Bank of England.

In the last couple of years, the global economy, including the UK, has been hit by an inflationary shock that has triggered a cost-of-living crisis.

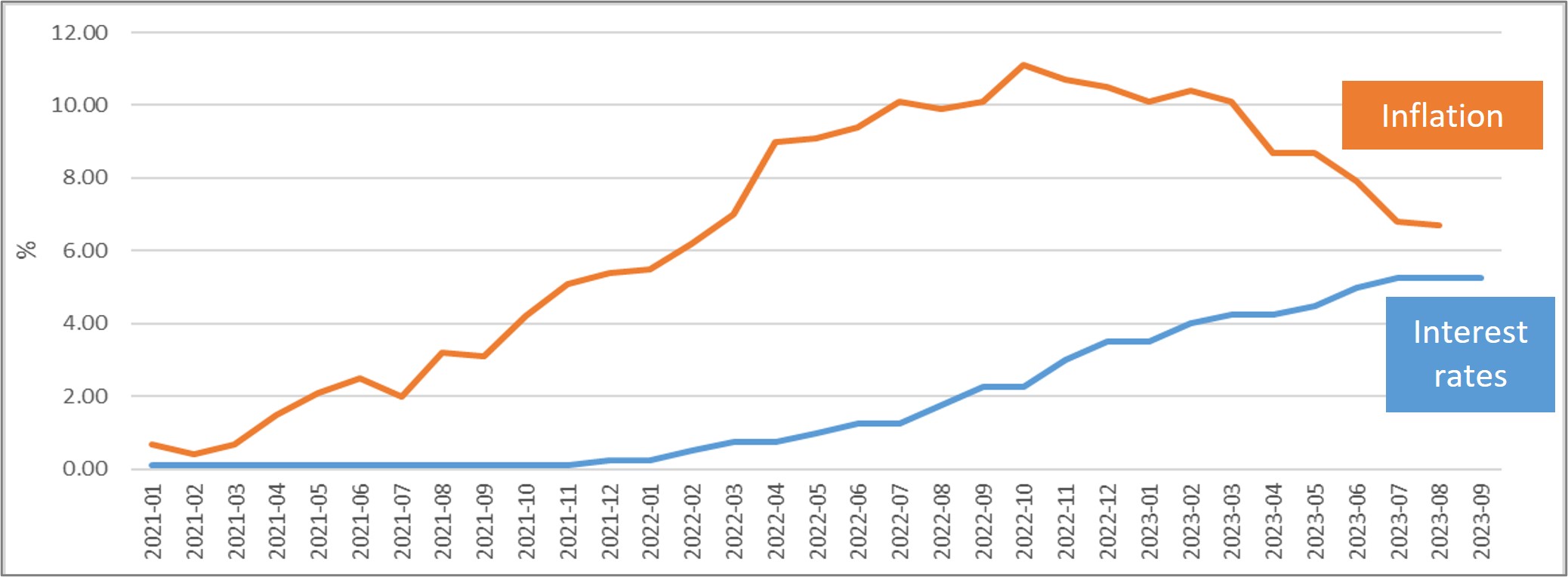

The inflation has remained well above the 2% target of the Bank of England during this period and at its peak, it was overshooting the target more than five folds. There are several reasons for this surge in inflation, the most significant include recovery and restoration of economic activity after COVID-19, disruption of the supply chain, increase in global energy and food prices and the Russia-Ukraine war.

To tackle inflation and deliver on its mandate of price stability i.e., to keep the annual rate of inflation at 2%, the Bank of England has tightened its monetary policy stance by raising interest rates. A similar strategy has been adopted by the European Central Bank and the US Federal Reserves.

The notion is that the high interest rates lead to a reduction in spending and aggregate demand and hence cool down the inflationary pressure. However, this strategy has many shortcomings as it hurts the economy.

Bank of England’s Policy rates and inflation in the United Kingdom: Source (ONS)

To understand why monetary tightening by increasing the interest rates isn’t the best strategy we need to look at the causes of inflation here. Firstly, the increase in inflation after the revival of economic activity post-pandemic was obvious.

During the pandemic, economic activity was very restrained and hence it was just that both economy and inflation were bouncing back from a deflationary period of economic contraction.

Second, the pandemic had disrupted the global supply chains but when the economic recovery started post-pandemic, the supply chains were not able to cope with the demand pressures and we had the problem of “supply chain bottleneck”. As obvious, it took a while, before the supply chains could keep up with the demand pressure.

Third, the tragic Russia-Ukraine war caused massive geopolitical and economic disruption and resulted in a sharp increase the global energy and food prices. There is also a fourth reason which is somewhat debatable i.e., greedflation. A study by the University of Massachusetts Amherst has reported that the increase in inflation is due to the higher profit margins set by firms with strong market power. This was found to be in the case of the Eurozone, although the Bank of England’s study concluded that there is little evidence of that being the case.

Besides the reasons for high inflation, an important issue is the appropriate response. In this regard, the Bank of England started a tightening cycle with 14 consecutive rate rises starting from 0.1% in December 2021 to a 15-year high of 5.25% in August 2023.

There was no logical ground to increase the rates as none of the causes of inflation that are set out here can be addressed by rate rises, however, the Bank of England like other central banks, felt pressured and to save its reputation, gave in.

We may acknowledge here that the Bank of England was in a difficult position as the decisions by the other large central banks, including the US Federal Reserve have spillover effects. To counter them, the Bank of England had to increase the rates and of course, there is an element of peer pressure too. When inflation is overshooting the target by many folds, it is obvious that the Bank of England will feel pressured and be tempted to react even if the reaction is not the best strategy in terms of unintended consequences for economic stability.

The increase in inflation led to a reduction in the real wage as the wage increases during the last two years were not at par with the inflation. On this aspect, the Bank of England’s governor argued that the workers should not ask for significant increases in their salaries.

This unsolicited advice was based on the notion of “wage-price spiral” which implies that wage increases lead to inflation which in turn makes workers demand even higher wages and hence this nexus causes a spiral. The empirical evidence suggests that such a spiral does not always hold, yet the economic case for higher wages was ignored.

On average, the real wage in the UK shrunk during the last couple of years. With hindsight, we can see that there was indeed no wage-price spiral as inflation has come down sharply. In the face of falling inflation, it was also not a good idea to raise rates because the monetary policy has lag effects and thus it can take months and months before rate change can have any meaningful impact on inflation.

One of the consequences of the Bank of England’s monetary tightening is that it results in all forms of cost of borrowing including the mortgage rates.

It is expected that the mortgage rate will continue to be high and will not return to ultra-low levels anytime soon. A large number of households are on fixed-rate mortgages and therefore the full effects of the monetary tightening are yet to pass through and materialise. Following the Federal Reserve, in the most recent decision, the Bank of England has decided to pause further rate rises.

This is indeed good news, however, it does not seem that the Bank will reverse its decisions which is not good news considering the weakening outlook of the UK economy. The Bank of England and the government may claim the credit for halving the inflation, even if there is little contribution by them!

Dr Muhammad Ali Nasir is an associate professor in Economics at the University of Leeds and visiting research fellow at the University of Cambridge. He holds a PhD in Economics and is greatly interested in the areas of Monetary Economics, Macroeconomics, Financial Economics and International Economics and Energy and Environmental Economics. His recent book is entitled “Off the Target: The Stagnating Political Economy of Europe and Post-Pandemic Recovery”. Currently, he is working on the challenges of macroeconomic policy formulation and issues around financial, economic and environmental stability, particularly in the post COVID-19 world.

Posted in: University news